The Portland Art Museum of Native American Art From the Pacific Northwest

The Pacific Northwest has ever enchanted me. For those unfamiliar, this is the surface area—also known as Cascadia—of Canada and the Us that encompasses Oregon, Washington, and British Colombia (plus debatably parts of their surrounding neighbours). With its towering, almost fluorescent light-green trees and mountains running through the landscape like veins, it is a destination that feels singularly live. I notice myself coming dorsum here again and again, each fourth dimension coming abroad breathless for more. Strangely enough, however, I had never delved besides securely into the Cascadian art scene. Of form I had visited gardens, land parks, and little tourist trap galleries on the coastlines, which are artful plenty in their ain right, but never a specific art museum.

I recently have been back in the PNW to visit my brother in Portland, Oregon. This progressive, diverse metropolis has an unofficial motto: "Keep Portland weird". And weird it is, simply in the all-time sense. Portland is inundation with creativity. Around every corner you will find street art, micro-breweries with designs on the bottles as hypnotic as the drinks themselves, and friendly faces every bit open up and eclectic equally the city in which they reside.

Many cultural heritage institutions around the United states have been closed due to lack of funding in the wake of COVID-19, just the Portland Art Museum is ane of the lucky ones that has managed to reopen. It was founded in 1892, is the oldest museum in the Pacific Northwest, and the seventh oldest museum in the United States. It is particularly distinguished for its collection of art of the First Nations peoples of North America. This was my first time visiting. The experience was exhilarating, especially later on months of non being able to encounter whatever art in person. I institute the collection to be original and hitting in its content, and was able to find some real gems.

VOLCANO! Mountain St. Helens in Art is the current exhibition on view at the museum, and commemorates the 40th anniversary of the Mount St. Helens volcanic eruption of 1980. Information technology is a celebration of nature with its subversive and regenerative capacities, too as artists' profound ability to nurture creativity with destruction. The exhibition's set-up poignantly delineates the overbearing sense of 'before and afterwards' that St. Helens evokes. It is set up upwards chronologically, beginning in the commencement room with gorgeous pre-contact Native American basalt and obsidian utilitarian objects, and catastrophe with the most recent gimmicky depictions of the volcano. Colour is used in this exhibition to denote the massive change that took place when St. Helens erupted—starting vivid, but abruptly fading to grey. In the second room, paintings from as early on as the mid-1840s provide a serene, pastoral depiction of the mountain. More often than not in lighter shades, the room feels bright, if a little boring. Though the artists' unique styles are evident, the paintings are too optimistic, too obviously. Pretty landscapes they may seem, just these works, for me, are tainted with Manifest Destiny and Romanticism. They scream, "Look at this cute mountain! And these beautiful trees! And rivers!". I desire to scream back, "That you lot stole!"…but I digress.

The next room is my favourite. It explodes with color. And this is no coincidence, as these are the artworks that depict the actual explosion on May 18thursday, 1980. The artworks are cute and terrible, as bright and circuitous as the eruption. 1 piece in detail was my favourite of the exhibition: Mary Davis' The Mountain Speaks— Softly. This dreamy painting captures the mountain's mystic qualities, with visible brushwork that feels ashy, foggy, as if the entity inside is literally speaking through its smoke. The deep blues and warm hues offset one another, a dichotomy that speaks to the violence and renewal of the blast. In the right hand corner, eyes glow through the ash—ane cool toned, ane warm toned. Through these glowing orbs, the duality of the spirit of St. Helens is meditated upon. There is not simply catastrophe here, but also rebirth and renewal.

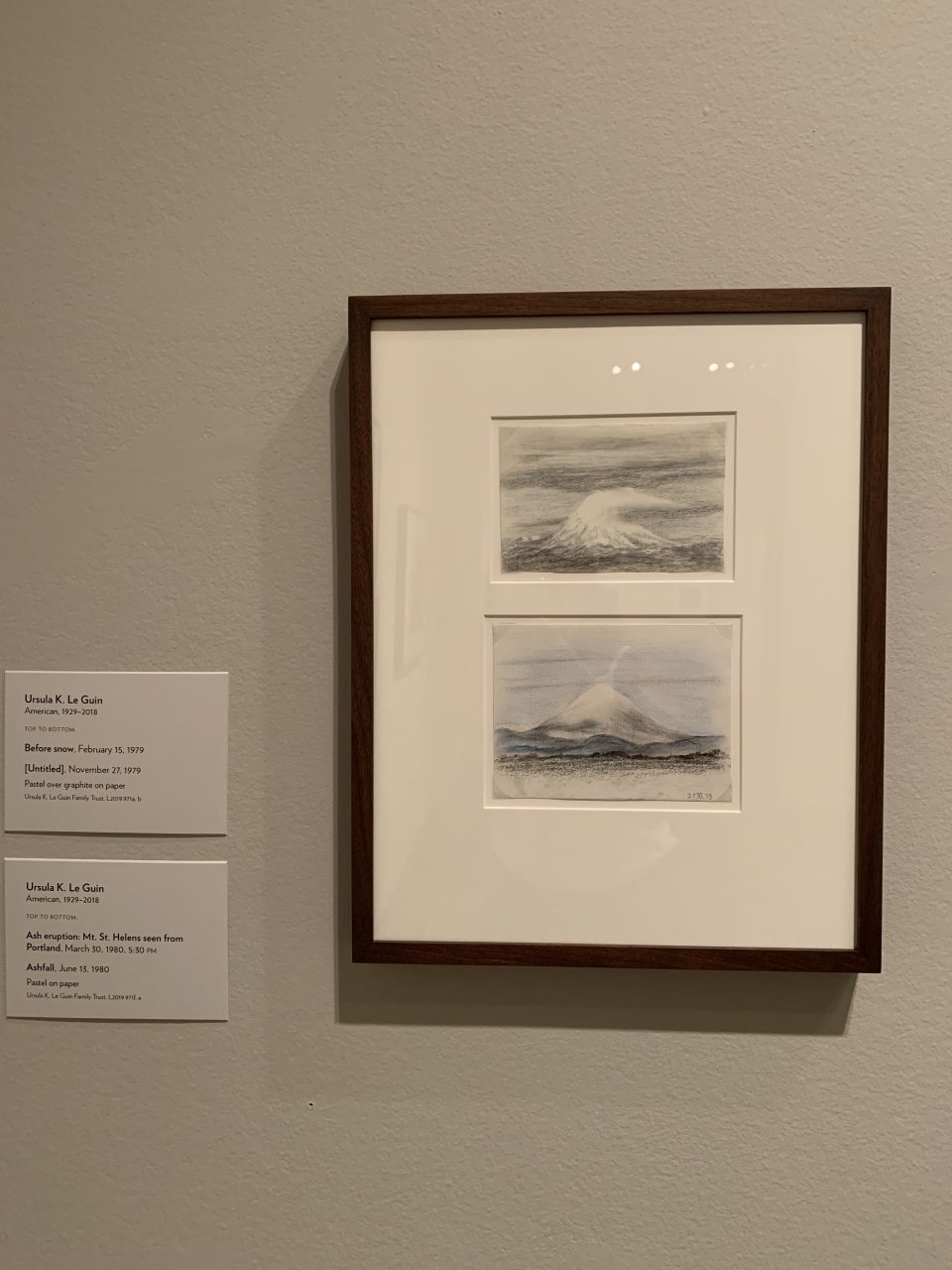

The terminal few rooms are the 'after'. Nearly every artwork in these rooms is in a shade of greyness. Photographs of trees blown to the ground, ash falling from the heaven, a lake upheaved from its previous location…information technology is sobering. The beauty of the boom thought possible in the previous room seems a ill joke when the desolate feeling in these pieces permeates the room. A favourite science fiction writer of mine, Ursula G. Le Guin, lived in Portland and documented both the pre and mail-eruption volcano using pastels. Her artworks are absorbing; St. Helens looks as if it belongs to an otherworld. It is like shooting fish in a barrel to imagine that Le Guin was inspired by this arid landscape in her writing. She is quoted, "…the fright I felt that day went deeper than the physical. Afterward driving miles up through the endless green vitality of a peachy wood, to turn a corner and enter a earth of grey ash, burnt stumps, and silence—from the complication of flourishing life into the awful simplicity of death: the fear I felt was metaphysical."

Ursula One thousand. Le Guin (American, 1929–2018).[Untitled], November 27, 1979. Pastel over graphite on newspaper. Ursula K. Le Guin Family unit Trust.

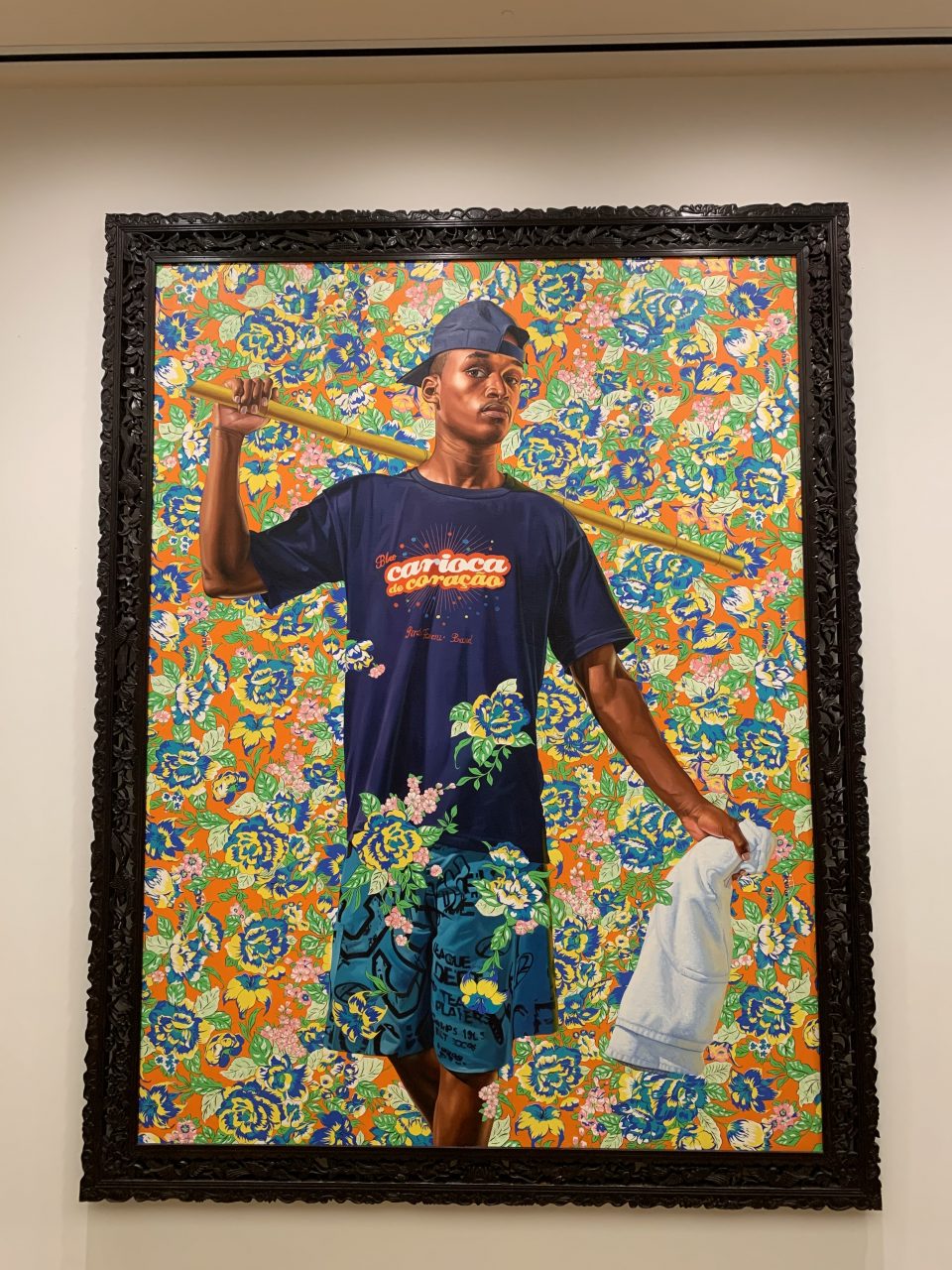

Moving along from the St. Helens exhibition, I didn't have much time to spare, equally museum slots were limited to an 60 minutes, and my slot was booked for the hour simply before closing. I wandered aimlessly for the xx minutes that I had left (although I do wish I had been a scrap more than proactive—I missed so much!). In a wide hallway on the bottom floor basement, was a portrait by artist Kehinde Wiley. I may have let loose a squeal; I had been wanting to encounter one of his artworks in person for nigh three years, since it was announced that Wiley would be painting Barack Obama's portrait. Indio Cuauhtémoc (The Globe Stage: Brazil) depicts an Afro-Brazilian human being in a heroic opinion. His wear is coincidental, but his pose and facial expression exude power, unapologetically grandiose and imperial. However, this is more than a celebration of the African diaspora; it is a harsh critique of colonialism. The tropical impress properties that surrounds him condemns the fetishisation of the 'tropical', something Americans are very guilty of in their clothing and vacation tastes. Cuauhtémoc was the concluding emperor of Tenochtitlán, and this painting echoes the stance of his statue, which resides in Rio de Janeiro. The emperor was executed past the Spanish, a nod by Wiley to the not-then-distant by colonialism that nonetheless pervades world cultures.

The adjacent room I found, simply upwards the stairs from the basement, was filled with European and American art from the plow of the 20th century. Amid the Rodin sculptures and Monets, I found an artist that I had never heard of before. Childe Hassam'due south mesmeric Nude in Sunlit Wood shows a side of Impressionism not ofttimes seen, with its absence of overbearing dissimilarity in colouring. A adult female stands nude in a forest, gazing through the trees. The trees move in the sunlight, almost glittering in the breeze, but the woman'due south stature is neutral, shaded by the canopy higher up. Indeed she could pass for a statue, with the trees billowing effectually her figure as she stands perfectly yet. The limited colour palette creates a natural ambience— of greenery, of gold lite and flesh, and undulating leaves.

The last room I visited (before I was nudged to leave at endmost) was filled with Abstraction. Hilla Rebay is best known for her career as an artist, but also as the co-founder and offset director of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. Her work Orange Accents was my favourite artwork in the Portland Fine art Museum. I will mostly let it speak for itself, only for me, it was a spiritual experience gazing at this painting. This is not surprising, as spirituality was both interwoven and integral to Rebay'due south fine art. Her vision was for viewers to be able to commune with the art in a 'museum-temple'—hence the co-founding of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. Like the Pacific Northwest, her Orange Accents feels alive. Geometric lines like anchors grasp onto the movement beneath them, struggling to concur onto Spirit itself, e'er-changing and evolving.

The Portland Art Museum is a hidden gem, just like Portland itself. If you e'er go the chance to visit the metropolis, I would highly recommend going to the museum. For now, on their website you lot tin find online exhibitions and myriad other features, such equally virtual reality film festivals, linked hither: https://portlandartmuseum.org/

johnstonparse1947.blogspot.com

Source: https://artgateblog.altervista.org/the-portland-art-museum-and-treasures-of-the-pacific-northwest/

0 Response to "The Portland Art Museum of Native American Art From the Pacific Northwest"

Post a Comment